Main Menu

“Sing a Song of Sixpence” is a well-known English nursery rhyme with uncertain origins, though it likely emerged during the 18th century. While some have inferred earlier references in literature, these are now considered coincidental rather than definitive sources.

One such example is found in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, written in around 1602, where Sir Toby Belch says to the clown, “Come on; there is a sixpence for you; let’s have a song.” Another oft-cited, though equally speculative, link appears in Bonduca, a play by Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, first performed around 1613 and published in their first folio in 1647, which includes the line, “Whoa, here’s a stir now! Sing a song o’ sixpence!”

For many years, the nursery rhyme as we know it was attributed to George Steevens, an English writer and noted Shakespearean scholar. This attribution stemmed from his supposed response to a poem by Henry James Pye, who was appointed Poet Laureate in 1790. Pye’s work, often characterised by its flowery language and patriotic tone, was widely mocked. His appointment was seen by many as a political reward rather than a recognition of literary merit.

After Pye presented an overly sentimental birthday poem to King George III, Steevens is said to have quipped:

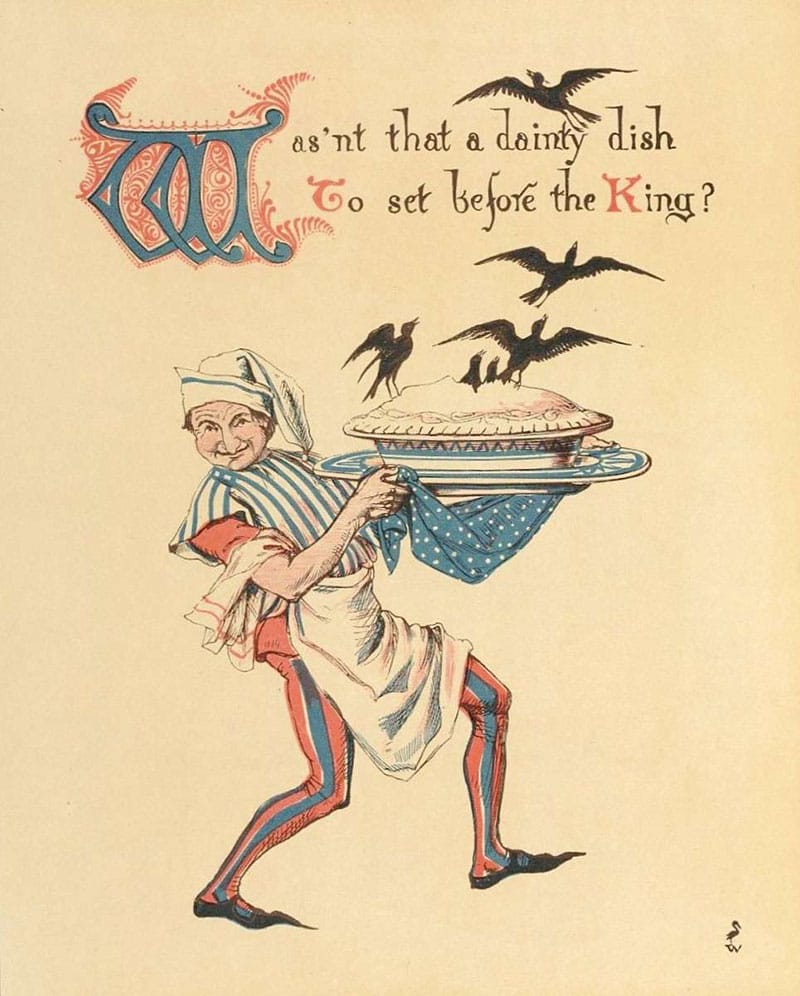

“And when the Pye was opened, the birds began to sing;

Was not that a dainty dish to set before the king?”

This clever pun quickly gained popularity. The essayist and poet Charles Lamb is known to have repeated the anecdote to his sister Mary’s nurse, Miss Sarah James, which helped further the association between Steevens and the rhyme.

However, the earliest known printed version of the rhyme predates this tale by nearly 50 years. It appeared in Tom Thumb’s Pretty Song Book, the oldest surviving collection of English nursery rhymes, published in London in 1744. That version reads:

Sing a Song of Sixpence,

A bag full of Rye,

Four and twenty Naughty Boys,

Baked in a Pye.

By 1780, the “naughty boys” of earlier versions had been replaced by blackbirds, and an additional verse had been introduced. In Gammer Gurton’s Garland: or, The Nursery Parnassus, edited by literary antiquary Joseph Ritson and published in 1784, a version close to the modern four-verse rhyme appears. This version ends with the now-familiar image of a blackbird attacking the unfortunate maid:

Sing a song of sixpence,

A pocket full of rye.

Four and twenty blackbirds

Baked in a pie.When the pie was opened,

The birds began to sing.

Wasn’t that a dainty dish

To set before the king?The king was in his counting house,

Counting out his money.

The queen was in the parlour,

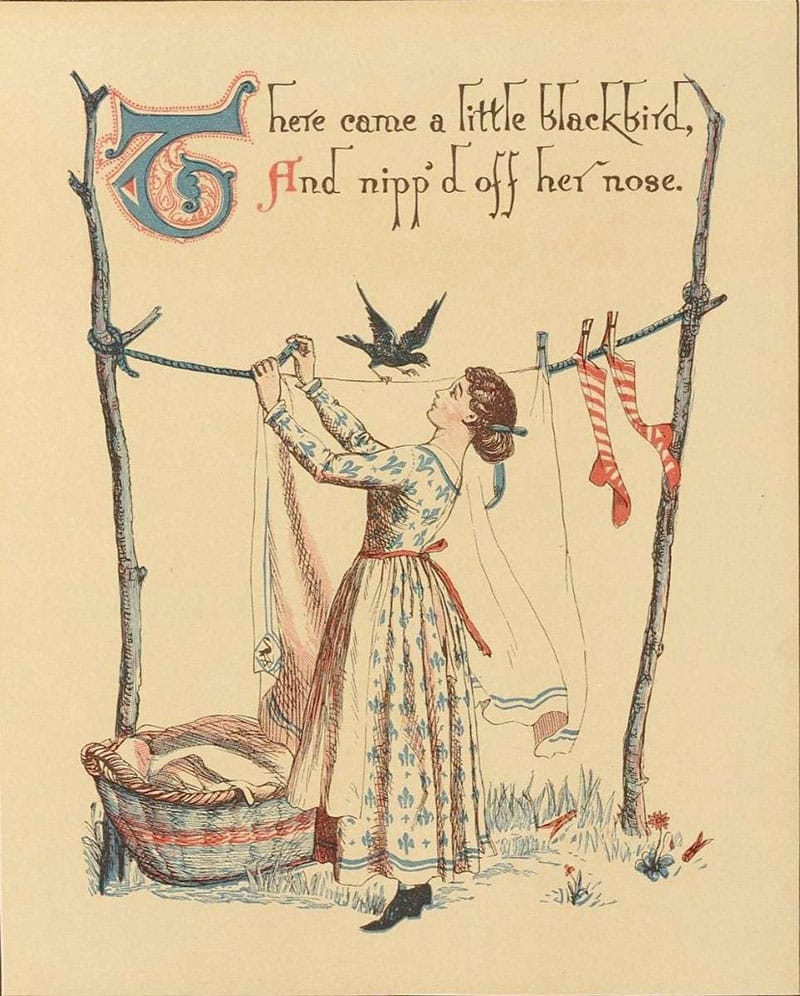

Eating bread and honey.The maid was in the garden,

Hanging out the clothes,

When down came a blackbird

And pecked off her nose.

Over time, additional verses were both added and removed. In The Nursery Rhymes of England, compiled by James Orchard Halliwell and published in 1842, a further verse appears:

Jenny was so mad,

She didn’t know what to do;

She put her finger in her ear,

And crackt it right in two.

Another variation was printed in Aunt Louisa’s Keepsake, published in 1866, offering a more whimsical resolution:

They sent for the king’s doctor,

Who sewed it on again.

He sewed it on so neatly,

The seam was never seen;

And the jackdaw, for his naughtiness,

Deservedly was slain.

People also amused themselves by inventing their own versions of the rhyme. One such risqué example, written by Margaret T. Shea in the 1930s, adds a mischievous twist:

Sing a song of sixpence, a pocket full of rye,

Four and twenty blackbirds baking in a pie,

When the pie was over, them all began to sing,

And wasn’t it a dandy dish to leave before the king?The king in his counting room counting out his money,

The queen in the parlour eating bread and honey,

The maid in the garden spreading out clothes,

Up comes a blackbird and done it on her nose.She swore by the bottle and glass that she’d never go to Mass

Till she’d play pitch and toss on the blackbird’s _____

As with many nursery rhymes, numerous theories have been proposed in an effort to assign deeper significance to “Sing a Song of Sixpence”. Some have suggested it alludes to the choirs of Tudor monasteries on the eve of their dissolution, while others claim it celebrates the printing of the English Bible, interpreting the blackbirds as symbols of the alphabet in pica type, a typographic unit roughly equal to one-sixth of an inch.

Other interpretations link the rhyme to the alleged corruption of the Romish clergy, a derogatory term used by Protestants during the Reformation to refer to Roman Catholic clergy, or to the workings of the solar system, with the 24 blackbirds representing the hours of the day, the king as the sun, and the queen as the moon.

In The Real Personages of Mother Goose published in 1950, Katherine Elwes Thomas offers a more political reading, drawing connections to Henry VIII, Katherine of Aragon, and Anne Boleyn. She interprets Henry as the king “counting the cash”, Katherine as the queen “eating bread and honey”, and Anne as the maid attacked by the blackbird, an allegory, she suggests, for Anne’s broken engagement to the son of the Duke of Northumberland.

However, Iona and Peter Opie, renowned folklorists and co-authors of the seminal 1951 work, The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, dismiss these interpretations. Applying rigorous modern research methods to the study of children’s literature, they concluded that none of these theories are supported by historical evidence.

A simpler, and more plausible, explanation is that the rhyme is meant to be taken literally. In earlier centuries, cooks often filled pies with ingredients that would seem unusual or unappetising by today’s standards, especially various types of birds. Recipes for blackbird pie were not uncommon; one example appears in Dressed Game and Poultry à La Mode, which describes a pie filled with stuffed blackbirds and fried rump steak, sealed beneath a puff pastry crust.

But this still doesn’t explain how the blackbirds could fly away after being baked in a pie.

To understand this curious detail, we must look back to the medieval era and its fascination with pies. At the time, pies were made with a thick, inedible crust known as a coffin, a sturdy pastry shell that functioned much like an ovenproof dish. These crusts were often pre-baked and then filled, rising during baking to form a pot-like shape, which is where the term pot pie originates.

While peasants used pies as a practical way to use up leftovers, the upper classes turned them into extravagant displays of wealth, encasing game, fowl, and fish, often flavoured with exotic fruits and spices. For an added spectacle at grand feasts, cooks would bake a pie filled with bran or flour, then cut a hole in the base after baking and insert live animals, such as birds or frogs, so that when the pie was served and opened, the creatures would leap or fly out, much to the amusement of the guests.

In a 1598 Italian cookery book with the wonderfully elaborate title Epulario, or The Italian Banquet: wherein is shewed the manner how to dress and prepare all kinds of flesh, fowl, or fish. As also how to make sauces, tarts, pies, &c., after the manner of all countries. With an addition of many other profitable and necessary things, translated from Italian into English, there appears a recipe for just such a pie.

To make Pies that the Birds may be aliue in them, and flie out when it is cut vp.

Make the coffin of a great Pie or pasty, in the bottome whereof make a hole as big as your fist, or bigger if you will, let the sides of the coffin bee somewhat higher then ordinary Pies, which done, put it full of flower and bake it, and being baked, open the hole in the bottome, and take out the flower. Then hauing a Pie of the bignesse of the hole in the bottome of the coffin aforesaid, you shal put it into the coffin, withall put into the said coffin round about the aforesaid Pie as ma∣ny small liue birds as the empty coffin will hold, besides the Pie aforesaid. And this is to be done at such time as you send the Pie to the table, and set before the guests: where vncoue∣ring or cutting vp the lid of the great Pie, all the Birds will flie out, which is to delight and pleasure shew to the company. And because they shall not bee altogether mocked, you shall cut open the small Pie, and in this sort you may make many others, the like you may do with a Tart.

In The Accomplisht Cook, published in 1685, Robert May, an English professional chef who trained in France, includes a recipe for a “Bride Pye”, an elaborate dish considered a predecessor of the modern wedding cake. Rather than a single pie, it was a collection of pies, each filled with a variety of luxurious ingredients such as eggs, butter, sweetbreads, oysters, stuffed larks, pickled mushrooms, artichokes, dried fruit and nuts, wine, spices, and lemons.

The centrepiece of the dish was designed to surprise and amuse wedding guests. May describes it as follows:

You may bake the middle one full of flour; it being bak’t and cold, take out the flour in the bottom, and put in live birds, or a snake, which will seem strange to the beholders when the pie is cut up at the Table. This is only for a Wedding, to pass away the time.

Medieval pies were even sometimes filled with much more than birds. At the Feast of the Pheasant, a lavish banquet hosted by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, on 17 February 1454 in Lille to rally support for a crusade against the Turks, who had captured Constantinople the previous year, an enormous pie was presented containing 24 musicians, who emerged playing their instruments to entertain the assembled guests.

In an episode of Heston’s Feasts, a Channel 4 series broadcast in 2009, experimental chef Heston Blumenthal set out to recreate “four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie”. To construct the enormous pie crust, he used 40 kilograms of lard and 80 kilograms of flour mixed with water, a project so large it required the use of a builder’s yard, industrial tools, and a pottery kiln to bake it.

Inside the huge crust, Blumenthal placed a series of smaller, edible pies. These were filled with confit pigeon legs cooked in duck fat, combined with cornichons, carrots, celeriac, anchovies, truffle, and a variety of herbs and spices. Each pie was then topped with sous-vide pigeon breast, artichoke hearts, and baby onions before the lid was added.

After learning that blackbirds are a protected species in the UK, Blumenthal substituted homing pigeons, another bird commonly eaten in medieval times. Early attempts at the grand reveal were unsuccessful, as the pigeons refused to fly out of the pie. Eventually, they were trained to fly toward cages suspended from the ceiling. When the pie was opened during the final presentation, the homing pigeons soared out, only to defecate on the celebrity diners below, adding an unintended but memorable twist to the spectacle.